BIOLOGICA BLOG

Περιοδοντίτιδα και Alzheimer, πώς συνδέονται μεταξύ τους;

Porphyromonas gingivalis, το ένοχο βακτήριο.

Στοματική υγιεινή, η ασπίδα μας.

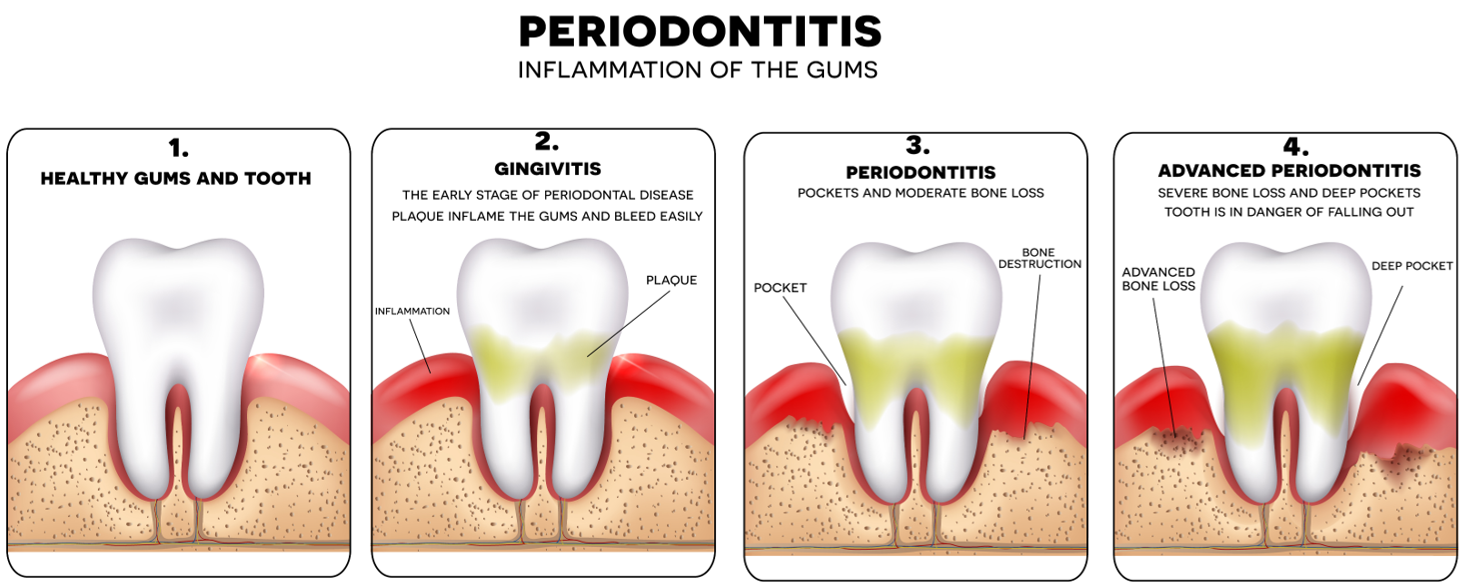

Τα βακτήρια αυτά ονομάζονται Porphyromonas gingivalis και εμπλέκονται στην περιοδοντίτιδα, την πιο σοβαρή μορφή περιοδοντικής νόσου. Τα νέα ευρήματα δείχνουν για άλλη μία φορά τη σημασία που έχει η καλή στοματική υγιεινή για ολόκληρο τον οργανισμό.«Η στοματική υγιεινή είναι άκρως σημαντική καθ’ όλη τη διάρκεια της ζωής όχι μόνο επειδή χαρίζει ένα όμορφο χαμόγελο αλλά κυρίως επειδή μειώνει τον κίνδυνο πολλών σοβαρών νόσων» ανέφερε ο επικεφαλής της ερευνητικής ομάδας Γιαν Ποτέμπα, καθηγητής στην Οδοντιατρική Σχολή του Πανεπιστημίου της Λούισβιλ στο Κεντάκι και διευθυντής του Τμήματος Μικροβιολογίας στο Πανεπιστήμιο Jagiellonian στην Κρακοβία της Πολωνίας, και προσέθεσε: «Ατομα που αντιμετωπίζουν γενετικό κίνδυνο για ρευματοειδή αρθρίτιδα ή νόσο Αλτσχάιμερ πρέπει να είναι πολύ προσεκτικά ώστε να μην εμφανίσουν περιοδοντική νόσο».Παρότι προηγούμενες μελέτες είχαν εντοπίσει την παρουσία του σε δείγματα που είχαν ληφθεί από τον εγκέφαλο ασθενών με νόσο Αλτσχάιμερ, η ομάδα του καθηγητή Ποτέμπα ανακάλυψε τις πιο ισχυρές ως σήμερα ενδείξεις σχετικά με το ότι το βακτήριο μπορεί πράγματι να συμβάλλει στην ανάπτυξη της συγκεκριμένης νόσου.

Τα στοιχεία αυτά μάλιστα παρουσιάστηκαν από τον καθηγητή κατά τη διάρκεια συνεδρίου για την Πειραματική Βιολογία που έλαβε χώρα στο Ορλάντο της Φλόριδας από τις 6 ως τις 9 Απριλίου.Οι ερευνητές συνέκριναν δείγματα εγκεφαλικού ιστού που ελήφθησαν μετά θάνατον από άτομα με ή χωρίς Αλτσχάιμερ και τα οποία ήταν περίπου ίδιας ηλικίας όταν απεβίωσαν. Ανακάλυψαν ότι το P. gingivalis εντοπιζόταν πιο συχνά στα δείγματα των ασθενών με Αλτσχάιμερ – αυτό αποδεικνυόταν μέσω του γενετικού «αποτυπώματος» του βακτηρίου καθώς και της παρουσίας των τοξινών-«κλειδιών» του (ονομάζονται gingipains). Από το στόμα στον εγκέφαλο. Στη συνέχεια οι επιστήμονες διεξήγαγαν πειράματα σε ποντίκια, τα οποία έδειξαν ότι το P. gingivalis μπορεί να μεταφερθεί από το στόμα στον εγκέφαλο καθώς και ότι αυτή η «μετανάστευση» μπορεί να μπλοκαριστεί από χημικά που αλληλεπιδρούν με τις gingipains.

Να σημειωθεί ότι ένα πειραματικό φάρμακο το οποίο μπλοκάρει τις τοξίνες και έχει την κωδική ονομασία COR388 βρίσκεται σε πρώτη φάση κλινικών δοκιμών για τη νόσο Αλτσχάιμερ. Οι ερευνητές σημειώνουν επίσης ότι το P. gingivalis παίζει ρόλο στην αυτοάνοση νόσο ρευματοειδή αρθρίτιδα, καθώς και στην πνευμονία από εισρόφηση, μια σοβαρή λοίμωξη των πνευμόνων που προκαλείται από εισρόφηση τροφής ή σάλιου και είναι αρκετά συχνή σε ηλικιωμένα άτομα. «Οι κύριες τοξίνες του P. gingivalis, τα ένζυμα που το βακτήριο χρειάζεται για να επιτελέσει τα «διαβολικά» καθήκοντά του, αποτελούν καλούς στόχους για πιθανές νέες παρεμβάσεις ενάντια σε πλήθος νόσων» σημείωσε ο καθηγητής Ποτέμπα. Εξήγησε ότι «η ομορφιά τέτοιων παρεμβάσεων σε σύγκριση με τα αντιβιοτικά είναι πως οι νέες παρεμβάσεις που μελετώνται στοχεύουν μόνο τα «κακά» βακτήρια αφήνοντας ανέπαφα τα καλά βακτήρια τα οποία χρειαζόμαστε για τη σωστή λειτουργία του οργανισμού». Περίπου ένα στα πέντε άτομα κάτω των 30 ετών εμφανίζουν έστω και χαμηλά επίπεδα του βακτηρίου στα ούλα τους. Παρότι δεν είναι επιβλαβές για τα περισσότερα άτομα, αν πολλαπλασιαστεί σε μεγάλους αριθμούς οδηγεί το ανοσοποιητικό σύστημα σε φλεγμονή που εκδηλώνεται με ερυθρότητα, οίδημα, αιμορραγία και διάβρωση του ιστού των ούλων. Και σαν να μην έφταναν όλα αυτά, το P. gingivalis κάνει και τα καλά βακτήρια του στόματος να αποκτήσουν… κακό χαρακτήρα και να αυξήσουν περαιτέρω την ανοσολογική απόκριση.

Πρόληψη και αποτροπή του βακτηρίου.

Τα βακτήρια μπορούν να ταξιδέψουν από το στόμα στην κυκλοφορία του αίματος μέσω καθημερινών δραστηριοτήτων όπως το μάσημα της τροφής ή το βούρτσισμα των δοντιών. Ο καλύτερος τρόπος ώστε να αποτραπεί το P. gingivalis να τεθεί εκτός ελέγχου είναι μέσω του τακτικού βουρτσίσματος των δοντιών και της χρήσης οδοντικού νήματος, καθώς και μέσω των επισκέψεων στον οδοντίατρο τουλάχιστον μία φορά τον χρόνο, τόνισε ο καθηγητής Ποτέμπα. Συμπλήρωσε ότι οι καπνιστές και τα ηλικιωμένα άτομα αντιμετωπίζουν αυξημένο κίνδυνο λοίμωξης. Εκτιμάται ότι και γενετικοί παράγοντες παίζουν ρόλο στην εμφάνιση περιοδοντίτιδας εξαιτίας του βακτηρίου, ωστόσο δεν έχουν γίνει ακόμη πλήρως κατανοητοί από τους επιστήμονες.

Βιβλιογραφία - Credits

- ^ Naito M, Hirakawa H, Yamashita A, et al. (August 2008). “Determination of the Genome Sequence of Porphyromonas gingivalis Strain ATCC 33277 and Genomic Comparison with Strain W83 Revealed Extensive Genome Rearrangements in P. gingivalis“. DNA Res. 15 (4): 215–25. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn013. PMC 2575886. PMID 18524787.

- ^ Africa, Charlene; Nel, Janske; Stemmet, Megan (2014). “Anaerobes and Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy: Virulence Factors Contributing to Vaginal Colonisation”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11(7): 6979–7000. doi:10.3390/ijerph110706979. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4113856. PMID 25014248.

- ^ Irshad M, van der Reijden WA, Crielaard W, Laine ML (2012). “In vitro invasion and survival of Porphyromonas gingivalis in gingival fibroblasts; role of the capsule”. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.). 60 (6): 469–76. doi:10.1007/s00005-012-0196-8. PMID 22949096.

- ^ Potempa, Jan; Dragunow, Mike; Curtis, Maurice A.; Faull, Richard L. M.; Reynolds, Eric C.; Walker, Glenn D.; Hasturk, Hatice; Adamowicz, Karina; Hellvard, Annelie (2019-01-01). “Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors”. Science Advances. 5 (1): eaau3333. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau3333. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6357742. PMID 30746447.

- ^ Wegner, N, Wait R, Sroka A, Eick S, Nguyen KA, Lundberg K, Kinloch A, Culshaw S, Potempa J, Venables PJ (September 2010). “Peptidylarginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis citrullinates human fibrinogen and α-enolase: Implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis”. Arthritis Rheum. 62 (9): 2662–2672. doi:10.1002/art.27552. PMC 2941529. PMID 20506214.

- ^ Berthelot JM, Le Goff B (2010). “Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease”. Joint Bone Spine. 77 (6): 537–41. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.04.015. PMID 20646949.

- ^ Ogrendik M, Kokino S, Ozdemir F, Bird PS, Hamlet S (2005). “Serum Antibodies to Oral Anaerobic Bacteria in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis”. MedGenMed. 7 (2): 2. PMC 1681585. PMID 16369381.

- ^ American Academy of Periodontology 2010 In-Service Exam, question A-85

- ^ Nelson KE, Fleischmann RD, DeBoy RT, Paulsen IT, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Gwinn M, Haft DH, Kolonay JF, Nelson WC, Mason T, Tallon L, Gray J, Granger D, Tettelin H, Dong H, Galvin JL, Duncan MJ, Dewhirst FE, Fraser CM (2003). “Complete genome sequence of the oral pathogenic bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis strain W83″. J. Bacteriol. 185 (18): 5591–601. doi:10.1128/jb.185.18.5591-5601.2003. PMC 193775. PMID 12949112.

- ^ Hutcherson JA, Gogeneni H, Yoder-Himes D, Hendrickson EL, Hackett M, Whiteley M, Lamont RJ, Scott DA (2015). “Comparison of inherently essential genes of Porphyromonas gingivalis identified in two transposon sequencing libraries”. Mol Oral Microbiol. 31 (4): 354–64. doi:10.1111/omi.12135. PMC 4788587. PMID 26358096.

- ^ Sheets, S; Robles-Price, A.; Mckenzie, R. (2012). “Gingipain-dependent interactions with the host are important for survival of Porphyromonas gingivalis“. Front. Biosci. 13 (13): 3215–3238. doi:10.2741/2922. PMC 3403687. PMID 18508429.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grenier, D; Imbeault, S; Plamondon, P.; Grenier, G.; Nakayama, K.; Mayrand, D. (2001). “Role of gingipains in growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the presence of human serum albumin”. Infect Immun. 69 (8): 5166–5172. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.8.5166-5172.2001. PMC 98614. PMID 11447200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Furuta, N; Takeuchi, H.; Amano, A (2009). “Entry of Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles into epithelial cells causes cellular functional impairment”. Infect Immun. 77 (11): 4761–70. doi:10.1128/IAI.00841-09. PMC 2772519. PMID 19737899.

- ^ Meuric V, Martin B, Guyodo H, Rouillon A, Tamanai-Shacoori Z, Barloy-Hubler F, Bonnaure-Mallet M (2013). “Treponema denticola improves adhesive capacities of Porphyromonas gingivalis“. Mol Oral Microbiol. 28 (1): 40–53. doi:10.1111/omi.12004. PMID 23194417.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kubinowa, M; Hasagawa, Y.; Mao, S (2008). “P. gingivalis accelerates gingivial epithelial cell progression through the cell cycle”. Microbes Infect. 10 (2): 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2007.10.011. PMC 2311419. PMID 18280195.

- ^ McAlister, A.D.; Sroka, A; Fitzpatrick, R. E; Quinsey, N.S; Travis, J.; Potempa, J; Pike, R.N (2009). “Gingipain enzymes from Porphyromonas gingivalis preferentially bind immobilized extracellular proteins: a mechanism favouring colonization?”. J. Periodontal Res. 44 (3): 348–53. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01128.x. PMC 2718433. PMID 18973544.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Vincents, Bjarne; Guentsch, Arndt; Kostolowska, Dominika; von Pawel-Rammingen, Ulrich; Eick, Sigrun; Potempa, Jan; Abrahamson, Magnus (October 2011). “Cleavage of IgG1 and IgG3 by gingipain K from Porphyromonas gingivalis may compromise host defense in progressive periodontitis”. FASEB Journal. 25 (10): 3741–3750. doi:10.1096/fj.11-187799. PMC 3177567. PMID 21768393.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grenier, D; Tanabe, S (2010). “Porphyromonas gingivalis Gingipains Trigger a Proinflammatory Response in Human Monocyte-derived Macrophages Through the p38α Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Signal Transduction Pathway”. Toxins (Basel). 2 (3): 341–52. doi:10.3390/toxins2030341. PMC 3153194. PMID 22069588.

- ^ Khalaf, Hazem; Bengtsson, Torbjörn (2012). Das, Gobardhan (ed.). “Altered T-Cell Responses by the Periodontal Pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis“. PLOS ONE. 7 (9): 45192. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…745192K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045192. PMC 3440346. PMID 22984628.

- ^ Potempa, Jan; Dragunow, Mike; Curtis, Maurice A.; Faull, Richard L. M.; Reynolds, Eric C.; Walker, Glenn D.; Hasturk, Hatice; Adamowicz, Karina; Hellvard, Annelie (2019-01-01). “Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors”. Science Advances. 5 (1): eaau3333. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau3333. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6357742. PMID 30746447.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Singh, A; Wyant, T; et al. (2011). “The capsule of Porphyromonas gingivalis leads to a reduction in the host inflammatory response, evasion of phagocytosis, and increase in virulence”. Infect Immun. 79 (11): 4533–4542. doi:10.1128/IAI.05016-11. PMC 3257911. PMID 21911459.

- ^ D’Empaire, G; Baer, M.T; et al. (2006). “The K1 serotype capsular polysaccharide of Porphyromonas gingivalis elicits chemokine production from murine macrophages that facilitates cell migration”. Infect Immun. 74 (11): 6236–43. doi:10.1128/IAI.00519-06. PMC 1695525. PMID 16940143.

- ^ Gonzalez, D; Tzianabos, A.O.; et al. (2003). “Immunization with Porphyromonas gingivalis Capsular Polysaccharide Prevents P. gingivalis-Elicited Oral Bone Loss in a Murine Model”. Infection and Immunity. 71 (4): 2283–2287. doi:10.1128/IAI.71.4.2283-2287.2003. PMC 152101. PMID 12654858.

- ^ Tsuda, K; Amano, A; et al. (2005). “Molecular dissection of internalization of Porphyromonas gingivalis by cells using fluorescent beads coated with bacterial membrane vesicle”. Cell Struct Funct. 30 (2): 81–91. doi:10.1247/csf.30.81. PMID 16428861.

- ^ Hajishengallis, G; Wang, M.; et al. (2006). “Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae proactively modulate β2integrin adhesive activity and promote binding to and internalization by macrophages”. Infect. Immun. 74 (10): 5658–5666. doi:10.1128/IAI.00784-06. PMC 1594907. PMID 16988241.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lin, X; Wu, J.; et al. (2006). “Porphyromonas gingivalisminor fimbriae are required for cell-cell interactions”. Infect Immun. 74 (10): 6011–6015. doi:10.1128/IAI.00797-06. PMC 1594877. PMID 16988281.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Park, Y; Simionato, M; et al. (2005). “Short fimbriae of Porphyromonas gingivalis and their role in coadhesion with Streptococcus gordonii”. Infect Immun. 73 (7): 3983–9. doi:10.1128/IAI.73.7.3983-3989.2005. PMC 1168573. PMID 15972485.

- ^ Love, R; McMillan, M.; et al. (2000). “Coinvasion of Dentinal Tubules by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus gordonii Depends upon Binding Specificity of Streptococcal Antigen I/II Adhesin”. Infect. Immun. 68 (3): 1359–65. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.3.1359-1365.2000. PMC 97289. PMID 10678948.

- ^ Pierce, D.L; Nishiyama, S.; et al. (2009). “Host adhesive activities and virulence of novel fimbrial proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis”. Infect. Immun. 77 (8): 3294–301. doi:10.1128/IAI.00262-09. PMC 2715668. PMID 19506009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hajishengallis, G; Liang, S.; et al. (2011). “A Low-Abundance Biofilm Species Orchestrats Inflammatory Periodontal Disease through the Commensal Microbiota and the Complement Pathway”. Cell Host Microbe. 10 (5): 497–506. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. PMC 3221781. PMID 22036469.

- ^ Wang M, Liang S, Hosur KB, Domon H, Yoshimura F, Amano A, Hajishengallis G (2009). “Differential virulence and innate immune interactions of Type I and II fimbrial genotypes of Porphyromonas gingivalis“. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 24 (6): 478–84. doi:10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00545.x. PMC 2883777. PMID 19832800.

- ^ Liang, S; Krauss, J.L.; et al. (2011). “The C5a receptor impairs IL-12-dependent clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis and is required for induction of periodontal bone loss”. J. Immunol. 186 (2): 869–77. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003252. PMC 3075594. PMID 21149611.

- ^ Hajishengallis, G; Wang, M.; et al. (2008). “Pathogen induction of CXCR4/TLR2 cross-talk impairs host defense function”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105 (36): 13532–7. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513532H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803852105. PMC 2533224. PMID 18765807.

- ^ Mao, S; Park, Y.; et al. (2007). “Intrinsic apoptotic pathways of gingival epithelial cells modulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis“. Cell Microbiol. 9 (8): 1997–2007. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00931.x. PMC 2886729. PMID 17419719.

- ^ Hajishengallis, G (2009). “Porphyromonas gingivalis-host interactions: open war or intelligent guerilla tactics?”. Microbes Infect. 11 (6–7): 637–645. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2009.03.009. PMC 2704251. PMID 19348960.

- ^ Darveau, R.P.; Hajishengallis, G.; et al. (2012). “Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease”. J. Dent. Res. 91 (9): 816–820. doi:10.1177/0022034512453589. PMC 3420389. PMID 22772362.

- ^ Guyodo H, Meuric V, Le Pottier L, Martin B, Faili A, Pers JO, Bonnaure-Mallet M (2012). “Colocalization of Porphyromonas gingivalis with CD4+ T cells in periodontal disease”. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 64 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695x.2011.00877.x. PMID 22066676.

- ^ Inagaki, S; Onishi, S.; et al. (2006). “Porphyromonas gingivalis vesicles enhance attachment, and the leucine-rich repeat BspA protein is required for invasion of epithelial cells by “Tannerella forsythia“”. Infect. Immun. 74 (9): 5023–8. doi:10.1128/IAI.00062-06. PMC 1594857. PMID 16926393.

- ^ Verma RK, Rajapakse S, Meka A, Hamrick C, Pola S, Bhattacharyya I, Nair M, Wallet SM, Aukhil I, Kesavalu L (2010). “Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola Mixed Microbial Infection in a Rat Model of Periodontal Disease”. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2010: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2010/605125. PMC 2879544. PMID 20592756.

- https://www.tovima.gr/2019/04/25/science/pos-ta-oula-mas-syndeontai-me-ti-noso-altsxaimer/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porphyromonas_gingivalis